Vestibular Migraine: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management

Article information

Abstract

Vestibular migraine (VM) remains a clinical challenge due to its heterogeneous presentation and the frequent absence of typical migraine features during vestibular episodes. Although many studies have adopted the diagnostic criteria defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD), interpretation of findings is often complicated by variability in how these criteria are applied across studies. VM is frequently underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, owing to its clinical overlap with other vestibular disorders. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the epidemiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and treatment strategies for VM. Particular emphasis is placed on distinguishing VM from other causes of vertigo to support accurate diagnosis and tailored management. By synthesizing current evidence, this review aims to improve clinical recognition, diagnostic precision, and therapeutic outcomes for patients with this under-recognized and often debilitating condition.

INTRODUCTION

Migraine and vertigo are both prevalent, each having an estimated annual prevalence of 17%.1,2 These conditions co-occur more frequently than would be expected by chance, indicating a comorbidity between the two.3 Many studies since 1984 have demonstrated the association between migraines and recurrent vertigo.4-9 Various terms have been used to describe dizziness originating from migraine, including migrainous vertigo, migraine-related vestibulopathy, vestibular migraine (VM), migraine-related (or associated) vertigo (or dizziness), benign recurrent vertigo, and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood. Among these, ‘migraine-related vestibulopathy’ and ‘VM’ emphasize the pathophysiological connection between the vestibular system and migraine, while the rest are descriptive terms. Benign paroxysmal vertigo is a pediatric condition marked by recurrent, transient episodes of vertigo in the absence of headache. It is widely regarded as an acephalic migraine variant or migraine equivalent, reflecting the early-life manifestation of migraine-related disorders. In 2004, Neuhauser and Lempert10 presented diagnostic criteria for migrainous vertigo, and in 2012, the Bárány Society modified these criteria to introduce ‘VM’ into the International Classification of Vestibular Disorders (ICVD).11-13 The International Headache Society recognized VM as a potential type of migraine in the appendix of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD), 3rd edition, published in 2018.12 If future studies using new diagnostic criteria provide sufficient evidence that VM is a subtype of migraine, it will be officially classified as a subtype of migraine in the ICHD-4.

The diagnostic challenge of VM often stems from its broad spectrum of clinical manifestations and the frequent absence of typical migraine headaches during episodes of vestibular symptoms. Although the ICHD-3 provides formal diagnostic criteria, the actual application of these criteria in clinical and research settings remains variable, leading to inconsistencies in diagnosis. Furthermore, many vestibular disorders can present with symptoms that mimic VM, complicating the diagnostic process. Therefore, this review focuses on clarifying the practical aspects of VM diagnosis and highlighting key vestibular conditions that must be considered in the differential diagnosis. By improving diagnostic accuracy, clinicians can better manage this under-recognized yet impactful condition.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

VM is the second most common cause of recurrent vertigo after benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), with an estimated annual prevalence of 1% to 3% in the adult population.14,15 It is well-known that migraine is more common among patients with vertigo than in controls, and vice versa. Specifically, during severe migraine attacks, where the pain intensity scores above 7 on the visual analogue scale, 47.5% of patients report symptoms of dizziness or vertigo.16 Clinic-based epidemiological studies indicate that about 10% of patients in headache clinics suffer from VM, and similarly, about 10% of patients in dizziness clinics are diagnosed with VM.3,17 Recent multicenter headache clinic studies in Korea also show that 10.3% and 2.5% of migraine patients were diagnosed with VM and probable VM, respectively.17 Considering the annual migraine prevalence of 17% in Korea,1 it is estimated that hundred thousands of Korea’s 40 million adults may suffer from VM. Despite its common occurrence and significant impact on healthcare utilization, VM remains a very under-recognized condition. The rate of diagnosis of VM in the general population and in patients referred to a vertigo center was only 10% and 20%, respectively.14,18

VM is approximately 3–4 times more common in women,14,15 and is more frequent in those with chronic migraine than in that with episodic migraine, and more in migraine with aura than in that without.16 VM can occur at any age, but in most patients, migraine symptoms precede the onset of vestibular symptoms. According to a study by Neuhauser et al.,8 the average age of onset for VM is 35 years, which is approximately 13 years later than that of migraine. This temporal gap suggests that vestibular symptoms may represent a later-stage development in the migraine trajectory. As patients age, migraine headache may evolve into symptoms such as vertigo, dizziness, or postural instability. Notably, in women, vestibular symptoms may emerge or become more prominent after menopause.19

DIAGNOSIS

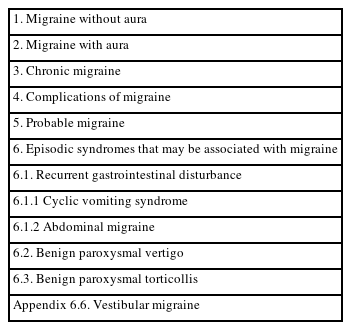

Diagnosing VM necessitates familiarity with the classification, diagnostic criteria, and clinical characteristics of migraine. The International Headache Society first categorized all headache disorders and established diagnostic criteria in 1988, with the latest update in 2018.12 The ICHD-3 organizes headaches into four Parts: Part I covers primary headaches, Part II deals with secondary headaches, Part III includes neuropathies & facial pains and other headaches, and Part IV is an appendix that assesses emerging headache disorders and criteria for potential inclusion in future editions. Currently, VM is categorized under the appendix as the sixth subtype of migraine, labeled ‘episodic syndromes that may be associated with migraine’ (Table 1), which typically encompasses symptoms like recurrent vomiting, abdominal pain, and vertigo in children.

Although the diagnostic criteria for migraine appear simple and clear, there can be considerable variation in headache characteristics, accompanying symptoms, intensity, and frequency among patients, and even within the same patient across different attacks. This variation can alter the diagnosis based on how the medical history is collected. Migraine can also phenotypically resemble tension-type headache, especially if migraineurs experience a mild attack or take pain medication early on. The term “migraine,” which implies one-sided headache, can lead to misdiagnosis; bilateral headaches are common in migraine, and many patients who describe their headaches as migraine may be experiencing primary stabbing headache or cluster headache.

The diagnostic criteria for migraine consist of four components: (A) recurrent attacks, (B) lasting 4–72 hours, (C) headache characteristics, and (D) accompanying symptoms. It is important to note that the duration of more than 4 hours applies when no painkillers are taken, as many migraine patients take painkillers at the onset or even during the prodromal phase, leading them to underestimate their headache duration as less than 4 hours. Regarding headache characteristics, probably moderate to severe intensity and worsening of headache due to daily activities are more crucial for diagnosis than being one-sided or pulsating. Migraine patients become hypersensitive to sensory stimuli such as visual, auditory, olfactory, and vestibular during a headache, with photophobia and phonophobia included in the diagnostic criteria. Photophobia and phonophobia encompass hypersensitivity/discomfort/worsening of the headache from light and sound. Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, osmophobia and vestibular symptoms are also common accompanying symptoms in migraine. About half of the patients report dizziness during migraine attacks. A study of 2,782 headache patients in Asia, including Korea, found that 55% of migraine patients reported dizziness.20 Dizziness is often non-rotational but can appear as rotational vertigo, especially when the headache intensity is high,16 and it is a significant disabling symptom along with nausea/vomiting.20 In cases of phonophobia or osmophobia, migraine patients commonly report discomfort not only from loud noises or bad smells but also from sounds of music or perfume scents. Gastrointestinal symptoms are among the most common and important accompanying features in the diagnosis of migraine. Asking whether a patient experiences headache when they have indigestion, in addition to inquiring about nausea or vomiting during headache attacks, can serve as a simple and effective screening tool for migraine. While the diagnostic criteria for migraine are strict, an accurate diagnosis requires a broader clinical perspective. This includes consideration of common triggers such as menstruation, a family history of headache, and the patient's response to medications containing triptans or caffeine.

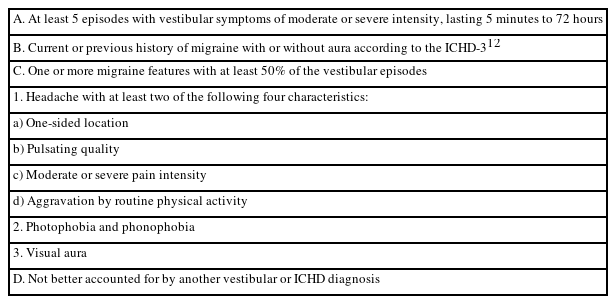

The current diagnostic criteria for VM in the ICVD by the Bárány Society were established in accordance with the framework of the ICHD’s diagnostic criteria (Table 2).13 It was based on the concept of ‘migrainous vertigo’ first proposed by Neuhauser et al.8 in 2001. Additionally, the term ‘migrainous vertigo’ was replaced with ‘VM’ to better emphasize vertigo caused by the pathophysiology of migraine. The ICVD includes a rather loose criterion known as ‘probable VM.’ Probable VM meets only one of the criteria B and C in the diagnostic criteria for VM.13 Some patients with VM may not recall or have a history of migraine, and vestibular symptoms may occur without a temporal association with migraine attacks. Probable VM may be included in a later version of the ICHD, when further evidence has accumulated.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

The primary obstacle in diagnosing VM lies in the ambiguity of vestibular symptoms. Patients frequently report various symptoms from different causes under the umbrella term “dizziness.” Additionally, distinguishing between rotational and non-rotational dizziness, along with postural instability, based on patient history can be challenging. Typically, if a patient complains of a sensation of ‘spinning’ or a ‘tilting illusion,’ it is considered vertigo originating from the vestibular system. If the complaints are of ‘lightheadedness,’ ‘unsteadiness or imbalance,’ or a sensation of ‘near fainting,’ they are regarded as non-vestibular dizziness. However, dizziness due to vestibular disorders may not always appear rotational, and patients with non-vestibular dizziness such as psychogenic dizziness may also report rotational symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish vestibular from non-vestibular dizziness through history taking alone.

The ICVD by the Bárány Society categorizes vestibular symptoms into vertigo, dizziness, vestibulo-visual symptoms, and postural symptoms, further subdividing vertigo and dizziness into spontaneous and triggered types.21 Vertigo is defined as an illusory sensation of movement of oneself or one's surroundings when no actual movement is occurring. Dizziness is the sensation of disturbed or impaired spatial orientation without a false or distorted sense of motion.21 Among the various vestibular symptoms, qualifying for a diagnosis of VM, include spontaneous vertigo, positional vertigo, visually-induced vertigo, head motion-induced vertigo, and head-motion induced dizziness with nausea, while excluding postural symptoms. The prevalence of vestibular symptoms in VM shows variation across different studies. In a large German study conducted via telephone interviews, 67% of participants with VM experienced spontaneous rotational vertigo, and 24% reported positional vertigo.14 Meanwhile, a multi-center headache clinic study in Korea found that head motion-induced dizziness with nausea was present in 37% of cases, spontaneous vertigo in 26%, positional vertigo in 22%, and head motion-induced vertigo in 15%.17 However, most patients with VM may complain of more than one vestibular symptom during VM episodes make it more complicated.22

During an attack of VM, auditory symptoms, nausea, and vomiting may occur but are not included in the diagnostic criteria because these symptoms are common in other vestibular disorders as well. Tinnitus, hearing loss, and a sensation of ear fullness are observed in up to 38% of patients, but the degree of hearing loss is mild and temporary.23 Many individuals with migraines report experiencing varying degrees of dizziness during their attacks.20 Therefore, only dizziness or vertigo that significantly interferes with daily activities is recognized as a vestibular symptom of VM.

The duration of vestibular episodes can vary widely between and within patients from a few seconds to several weeks. About 30% experience episodes lasting minutes, another 30% have attacks that persist for hours, and a further 30% suffer from episodes spanning several days. The remaining 10% experience brief attacks lasting only seconds, which frequently occur during head movements, visual stimulation, or positional changes of the head.8,24 Vestibular symptoms of VM can occur at any time between the prodrome and postdrome phases.25 Nearly thirty percent of VM attacks occur without headache,26 in which case other accompanying migraine symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, or osmophobia may be critical for diagnosis. VM is more common in migraine with aura16 but may occur without headache. Particularly in cases where vertigo occurs without headache, observation of the aura is important in diagnosing VM. Typical auras include visual, sensory, and speech disturbances, but only visual symptoms are included in the diagnostic criteria for VM. This is because other aura symptoms, such as sensory disturbances or speech difficulties, are often ambiguous for diagnosis, and most patients with these auras also have visual aura. Visual aura includes parts of the visual field that are not visible or flashing lights or zigzag lines that last less than an hour before disappearing on their own. One side of the visual field is usually affected, but aura can occur on both sides of the visual field. Many migraineurs complain of blurred or foggy vision during the headache, but the visual symptoms of visual aura usually precede the headache and change shape over several minutes, which is a distinguishing feature. Common triggers for VM include menstruation, lack of sleep, stress, red wine, and weather changes, similar to migraine triggers.22 Vestibular stimuli can also trigger migraines.27 Therefore, dizziness caused by other vestibular disorders can trigger migraine in patients with migraine, so care must be taken not to misdiagnose these cases as VM.

NEUROOTOLOGICAL FINDINGS

VM typically shows normal neurotological examination findings between attacks. During an attack, central signs such as gaze-evoked nystagmus, saccadic pursuit, central positional vertigo, and vertical spontaneous nystagmus may be observed.7,28,29 In such cases, it is essential to differentiate other central disorders, such as cerebellar degeneration. Although there are numerous studies utilizing tests such as the caloric vestibular test, dynamic posturography, vestibular evoked myogenic potentials, and subjective visual vertical in patients with VM, the results are inconsistent. Due to mixed findings of both abnormal and normal results, VM is diagnosed through history taking and neurotological examination.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The clinical presentation of VM is highly variable and can resemble a wide range of vestibular disorders that cause recurrent vertigo or chronic dizziness. As VM lacks definitive biomarkers or objective diagnostic tests, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring the careful elimination of alternative vestibular conditions. Furthermore, since vestibular stimuli themselves can trigger migraine attacks,27 it is essential to rule out primary vestibular disorders that may coexist with migraine and contribute to symptom overlap. In evaluating patients with suspected VM, clinicians must also consider the potential adverse effects of migraine preventive medications, as these may mimic or exacerbate vestibular symptoms. For example, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and tricyclic antidepressants are commonly used in migraine prevention but can induce orthostatic hypotension, leading to dizziness. Additionally, medication-induced drowsiness, or visual disturbances may be misinterpreted by patients as dizziness, further complicating clinical assessment.

The differential diagnosis of VM is broad, but the most frequently encountered conditions in clinical practice include BPPV, persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD), and Meniere’s disease (MD). Notably, these disorders are not only common but may also coexist with VM, making it critical to adopt a comprehensive diagnostic approach that considers comorbidity as well as symptom overlap. Accurate differentiation is key to guiding appropriate treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes.

1. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

BPPV is typically diagnosed through provocation testing. Nonetheless, its high prevalence, recurrent nature, and sometimes the absence of positional nystagmus during provocation maneuvers complicates its differentiation from VM, which can similarly trigger vertigo or dizziness with head movements. It is known that around 25% of patients with VM report episodic positional dizziness.14,17 Differential diagnosis becomes more complicated when VM presents with positional nystagmus.30 Moreover, around one-third of BPPV patients also report experiencing headaches, further blurring the lines between these conditions.31 When differential diagnosis is difficult, there are three practical approaches in clinical settings. First, if BPPV has been confirmed at least once in the past, it is likely to be a recurrence, particularly in elderly patients. Second, if vertigo recurs frequently and no positional vertigo and/or nystagmus is induced by provocation maneuvers, empirical treatment for migraine might be a realistic approach. Finally, since both conditions are very common, the possibility that both disorders might coexist should be considered.

2. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness

In 2017, the Bárány Society formalized the diagnostic criteria for PPPD based on a consensus of experts who reviewed three decades of research on related conditions such as phobic postural vertigo, space-motion discomfort, visual vertigo, and chronic subjective dizziness.32 The established criteria define PPPD as the presence of one or more symptoms of dizziness, unsteadiness, or non-spinning vertigo that are present on most days for at least 3 months. These symptoms are typically exacerbated by maintaining an upright posture, active or passive movement, and exposure to moving or complex visual environments. PPPD may be precipitated by conditions including peripheral or central vestibular disorders such as VM, as well as other medical illnesses or psychological distress. Notably, PPPD and VM share several clinical features. Both conditions are commonly triggered by movement and visual stimuli,12,32,33 and both are frequently associated with psychiatric comorbidities, particularly anxiety.32,34 These overlapping characteristics can complicate the clinical differentiation between PPPD and VM. While VM is typically episodic in nature—presenting with discrete attacks of vestibular symptoms often accompanied by migraine features—PPPD is defined by its persistent, though often fluctuating symptom course. However, in some cases, patients with frequent or poorly controlled VM may report dizziness that appears continuous, thereby mimicking PPPD. This symptomatic overlap can make accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment particularly challenging. Furthermore, comorbidity is also common, as some patients may concurrently meet the diagnostic criteria for both PPPD and VM, further obscuring diagnostic clarity.35

Given these complexities, a careful and comprehensive clinical evaluation is essential. Clinicians must assess not only the type and duration of vestibular symptoms but also their temporal patterns, potential triggers, psychological profile, and response to past treatments. Symptom diaries, structured interviews, and validated questionnaires may aid in distinguishing PPPD from VM.

In the future, advances in neurobiological understanding and the discovery of disease-specific biomarkers may further refine diagnostic accuracy and improve differentiation between VM and PPPD. Until then, clinical acumen and a longitudinal, patient-centered approach remain key to appropriate diagnosis and management.

3. Meniere’s disease

MD and VM share several overlapping clinical features, making differential diagnosis a common challenge in neuro-otological practice. Epidemiological studies suggest a bidirectional association between the two conditions, with a high prevalence of MD among migraine sufferers and vice versa. Patients exhibiting features of both MD and VM are frequently encountered in clinical settings.36,37 In patients with VM, cochlear symptoms typically associated with MD—such as fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and aural fullness—can occasionally occur. However, significant or progressive sensorineural hearing loss is rarely seen in VM. Conversely, patients with MD may experience migraine-like features, including headache, photophobia, or visual aura, although these symptoms are generally milder and less frequent than in typical migraine presentations.38

Differentiating between VM and early-stage MD can be particularly difficult, as auditory symptoms in MD may be subtle or absent during the initial phase. In such cases, serial audiometric testing and close clinical follow-up are essential to track the evolution of cochlear involvement. A general principle in differential diagnosis is that when recurrent vestibular symptoms fulfill the diagnostic criteria for both VM and MD, the diagnosis of MD should take precedence, particularly in the presence of audiometrically confirmed low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss. However, when patients clearly exhibit two distinct patterns of vertigo—one consistent with VM and another with MD—it is acceptable to assign both diagnoses concurrently. This dual diagnosis approach acknowledges the complex interaction between migraine and inner ear dysfunction, which may represent a continuum rather than discrete entities.

Emerging evidence supports the existence of a VM/MD overlap syndrome,39-41 which may reflect shared pathophysiological mechanisms, such as altered ion homeostasis, vascular dysregulation, or neurogenic inflammation within the inner ear. Future revisions of the ICHD may incorporate criteria for this overlap syndrome, which could enhance diagnostic accuracy and guide tailored treatment strategies. Until then, an individualized, multidisciplinary diagnostic approach—integrating vestibular history, audiometry, imaging, and migraine assessment—remains critical for optimal patient care.

TREATMENT

As with migraine, the treatment of VM can be broadly divided into acute and preventive approaches. However, research specific to VM treatment remains relatively limited.

For acute management, two small studies using zolmitriptan and rizatriptan failed to demonstrate the effectiveness of triptans, which are migraine-specific treatments, largely due to limited sample sizes and methodological limitations.42,43 Despite these findings, triptans may still be considered in cases where the duration of a VM attack consistently exceeds several hours. However, the clinical presentation of VM is highly variable, both between individuals and across attacks in the same patient. As a result, the current standard of care for acute VM largely focuses on symptomatic relief. This typically involves the use of benzodiazepines, antihistamines, and antiemetics to manage vertigo and associated symptoms.

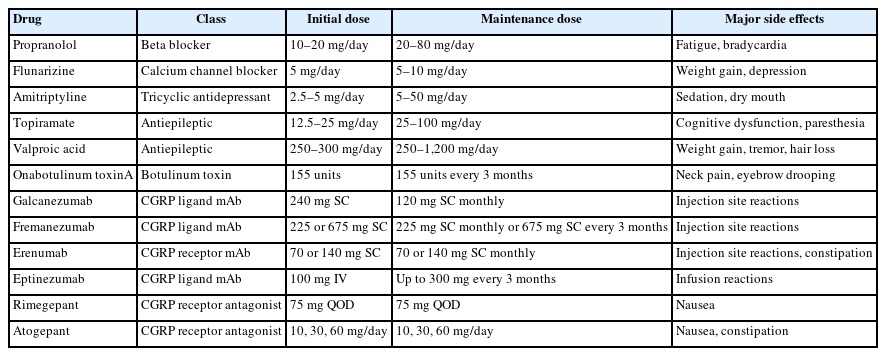

Regarding preventive treatment, well-designed randomized controlled trials specifically targeting VM are still lacking. Nevertheless, many of the medications that are effective in migraine prevention appear to offer benefit in VM as well. The choice of preventive therapy often depends on regional availability and regulatory approval. For example, flunarizine and lomerizine are the most commonly used calcium channel blockers for migraine prevention in Europe and Japan, respectively, but neither is approved for use in the United States. The most extensively studied and widely used preventive agents for migraine include propranolol, flunarizine, amitriptyline, topiramate, valproic acid, botulinum toxin, and more recently, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (Table 3).

A recent systematic review of randomized clinical trials on traditional oral preventives for VM found that valproic acid and flunarizine were effective in reducing the frequency of vertigo episodes and improving Dizziness Handicap Inventory scores.44 Among these traditional oral preventives, calcium channel blockers such as flunarizine, cinnarizine, and lomerizine possess antihistaminic properties, which may offer additional therapeutic advantages in the treatment of VM.45 However, traditional oral preventive medications are frequently associated with a range of adverse effects, including dizziness. Furthermore, based on the author’s clinical experience, patients with VM tend to be more susceptible to medication side effects. Therefore it may be more appropriate to use lower doses than those recommended by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN)46 or the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS)47 in this patient population.

CGRP monoclonal antibodies, recently introduced as migraine preventives, have shown promising results in VM.48-50 Emerging evidence suggests taht these agents are not only effective but also better tolerated than traditional options. Nevertheless, large-scale, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are urgently needed to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of various CGRP-targeted therapies in patients with VM.

CONCLUSIONS

VM remains a complex condition that is both underdiagnosed and challenging to diagnose effectively due to its diverse clinical presentation and overlapping symptoms with other vestibular disorders. While the ICHD-3 criteria for VM represent a valuable step forward in diagnosing a complex condition, they are limited by subjective symptom definitions, lack of empirical validation, rigid diagnostic thresholds, and insufficient accommodation for overlapping disorders or atypical presentations. These limitations of the ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for VM highlight the need for further research. It is hoped that advances in understanding the pathophysiology of VM and the identification of reliable biomarkers will lead to improved and more accurate diagnostic criteria in the future. To effectively manage patients with VM in clinical practice, it is essential to be able to accurately diagnose migraine and to have a comprehensive understanding of vestibular disorders that may mimic VM.

Notes

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: BKK; Writing–original draft: BKK; Writing–review & editing: BKK.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Byung-Kun Kim received honoraria as a moderator/speaker/advisor from Abbvie Korea, Teva-Handok, Lundbeck Korea, Pfizer Korea, Oganon Korea, Dong-A Pharm, YuYu Pharm, SK Pharm, and Ildong Pharm. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.