The Impact of Anti-Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Monoclonal Antibodies on Sleep Quality and Daytime Sleepiness in Migraine Patients: A Multicenter Study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to determine whether patients with migraine experience improvements in self-reported sleep quality and daytime sleepiness after starting monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) or its receptor, and to explore the association between treatment efficacy and improvements in sleep quality.

Methods

This prospective, multicenter, observational, longitudinal study was conducted across 12 headache centers. Adults with episodic or chronic migraine who began anti-CGRP mAb therapy were assessed at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months. Sleep quality and daytime sleepiness were evaluated using the Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-PT) and the Portuguese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS-PT), respectively.

Results

Of 118 enrolled patients, 109 completed the study (86.4% female; mean age, 43.6 years). A significant improvement in sleep quality was observed, with median PSQI-PT scores decreasing from 9 at baseline to 6 at 6 months (p<0.001). Daytime sleepiness also improved, with median ESS-PT scores decreasing from 7 to 6 (p=0.04). Migraine frequency decreased significantly, from a median of 13 to 4 monthly migraine days (p<0.001). Greater migraine improvement was independently associated with greater PSQI-PT improvement (p<0.001), whereas changes in ESS-PT were not correlated with treatment efficacy.

Conclusion

Anti-CGRP mAb therapy was associated with significant improvements in sleep quality, likely mediated through migraine relief. Changes in ESS-PT were not correlated with treatment efficacy, suggesting a possible interaction between migraine mechanisms and CGRP-mediated sleep–wake regulation. Future research should focus on clarifying the mechanisms underlying these associations.

INTRODUCTION

Migraine is a prevalent neurological disorder, affecting up to 15% of the adult population, with a higher prevalence in women. Beyond its significant personal and socio-economic impact, migraine is a leading cause of disability.1,2 The term ‘migraine burden’ refers to the overall impact of migraine on patients’ functional capacity, quality of life, and headache frequency and severity, encompassing both clinical and psychosocial dimensions.2

Sleep and migraine are closely interconnected.3,4 Many migraine sufferers report poor sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness, while disruptions in sleep patterns are well-known triggers for migraine attacks and may even contribute to its chronification.5,6

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is a key neuropeptide in migraine pathophysiology. The functional trigeminovascular system theory suggests that its activation during a migraine attack triggers the release of various neuropeptides, including CGRP. This cascade leads to neurogenic inflammation, vasodilation, and increased cerebral blood flow, ultimately resulting in pain.3,4,7 As a result, anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy has emerged as a promising approach to migraine treatment.8,9 Emerging evidence suggests that this same peptide may also be involved in circadian cycle and sleep regulation, particularly through maintaining wakefulness.10

Therefore, since CGRP may act as a common link between migraine pathophysiology and the sleep disturbances frequently associated with it, it is plausible that anti-CGRP mAb therapy could also improve sleep quality in migraine patients—either indirectly by reducing attack frequency or through a direct effect on CGRP. Other studies have tried to demonstrate this relation.11,12

The present study aims to determine whether patients with migraine experience an improvement in self-reported sleep quality and reduction of daytime sleepiness after initiating treatment with mAbs targeting CGRP or its receptor and assessing the relationship between treatment efficacy and sleep quality improvement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Health of Unidade Local de Saúde de Gaia e Espinho on March 28, 2023 (approval number 42/2023-1) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in the study.

2. Study design and population

This was a prospective, multicenter, observational, and longitudinal study conducted between March 1, 2023, and December 31, 2023. Twelve headache centers were included. A detailed standardized study protocol was distributed to all centers prior to patient recruitment, defining inclusion/exclusion criteria, data collection instruments, visit timelines, and follow-up procedures. Before study initiation, all investigators and research staff participated in an online training session coordinated by the lead center (Unidade Local de Saúde de Gaia e Espinho), focusing on protocol adherence, correct administration of the Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-PT) and Portuguese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS-PT) questionnaires, and uniform interpretation of headache diaries. To ensure consistency, each site used identical electronic templates for data entry, and any protocol-related queries were resolved through monthly coordination meetings and direct communication with the central coordinating team.

The study included patients initiating mAb therapy against CGRP for the first time, which included fremanezumab (225 mg, monthly), galcanezumab (120 mg, monthly), and erenumab (70 or 140 mg, monthly). Participants were recruited from outpatient neurology clinics at participating hospitals, provided they met the eligibility criteria, and written informed consent was signed.

Inclusion criteria encompassed adults aged 18–70 years diagnosed with episodic or chronic migraine, according to The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition criteria, with at least 4 monthly migraine days. Patients starting anti-CGRP mAbs, either as monotherapy or in combination with stable preventive treatment, were eligible. Exclusion criteria included prior mAb treatment or contraindications to this therapy.

3. Data collection and analysis

Patients underwent assessments at baseline (T0) and follow-ups at 3 (T1) and 6 months (T2). Data collection included demographic and clinical characteristics, migraine frequency and severity, comorbid sleep disorders, and medication use. The PSQI-PT13 and ESS-PT14 were applied to evaluate subjective sleep quality and daytime sleepiness, respectively. Headache diaries were maintained to track migraine days, pain intensity, and medication use.

To reduce inter-rater variability, all questionnaires were administered by trained investigators using a unified instruction guide.

The primary endpoint was the change in PSQI-PT score at T2 compared to T0. Secondary endpoints included changes in PSQI-PT and ESS-PT scores at T1 and T2 and correlations between sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, and migraine frequency.

All collected data were anonymized, encrypted, and stored in a restricted-access database. Data were centrally reviewed by the lead center. External monitoring ensured compliance with study protocols and data integrity.

4. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the change in the PSQI-PT score from T0 to T2 after initiating treatment with mAbs targeting CGRP or its receptor. A PSQI-PT score ≤5 was considered the threshold for good sleep quality.

Secondary endpoints included the variation in PSQI-PT score at T1 compared to T0, as well as the variation in the ESS-PT score at T1 and T2, with an ESS-PT score ≤10 considered within the normal range. Additionally, correlations were analyzed between PSQI-PT scores and the average number of monthly migraine days at T1 and T2 of treatment, as well as between ESS-PT scores and the number of migraine days over the same period.

To address potential inflation of type I error due to multiple outcome testing, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction. A two-tailed adjusted p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Variables description

The study assessed demographic and clinical variables. Demographic variables included age, recorded as a continuous variable, sex as a nominal categorical variable, and body mass index (BMI) as a continuous variable. Clinical variables included the presence of previously diagnosed sleep disorders, classified and categorized ordinally according to “The American Academy of Sleep Medicine International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition,” and the use of sleep medication (defined any prescribed pharmacological agent used primarily for sleep initiation or maintenance, excluding over-the-counter supplements), recorded as a nominal categorical variable. The type of migraine, the specific mAb used, and the number of concurrent preventive medications were categorized ordinally. Changes in preventive treatment were assessed as a nominal categorical variable, while the number of monthly migraine days, the number of days with moderate or severe pain, and the number of days requiring acute pain medication were analyzed as continuous variables. The PSQI-PT and ESS-PT questionnaire scores were also recorded as continuous variables. Effective treatment (categorical variable) was defined as the reduction of monthly migraine days by at least 50% after T1–T2.

Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For non-normally distributed variables, comparisons across time points (T0, T1, and T2) were performed using the Friedman test followed by pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with FDR adjustment. Given the non-parametric distribution of most continuous variables, results are reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) rather than means with 95% confidence intervals, which are less appropriate for skewed data. The interquartile range (IQR) was calculated by subtracting the 25th percentile (Q1) from the 75th percentile (Q3), i.e. IQR = Q3 − Q1. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Correlations between continuous variables were explored using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. A multivariable linear regression model was used to assess predictors of PSQI-PT and ESS-PT changes, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, migraine subtype, and use of sleep medication.

In addition to demographic and migraine-related variables, the regression model included sleep medication use as a covariate, given its potential influence on subjective sleep measures. The presence of a diagnosed sleep disorder at T0 was explored descriptively and in subgroup analyses (Table 1) but was not entered in the multivariate model due to limited sample size per diagnostic category and risk of model overfitting. As PSQI and ESS change scores were calculated within subjects (T2−T0), T0 variability in sleep quality and sleepiness was inherently controlled for.

6. Data management

Data collected during the study were recorded anonymously in a specifically designed database. This database was stored in a restricted-access folder, encrypted, and password-protected, ensuring patient confidentiality and security.

RESULTS

1. Cohort characteristics

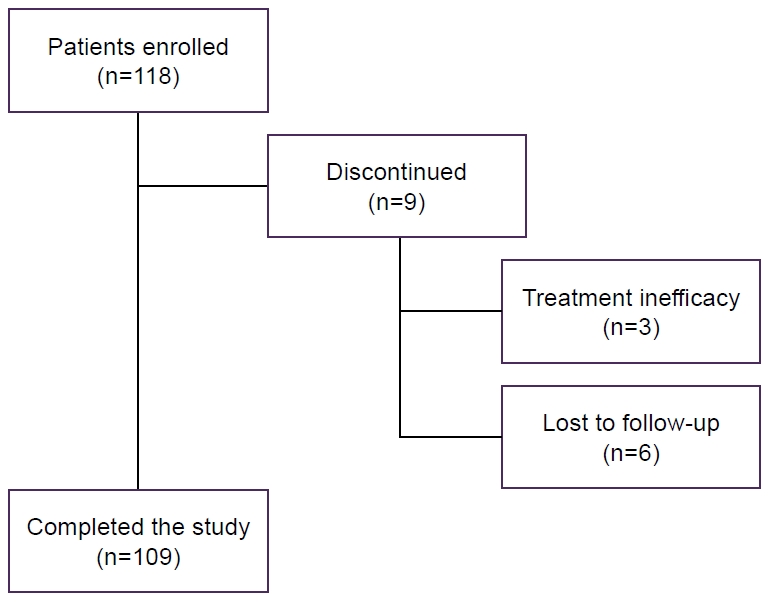

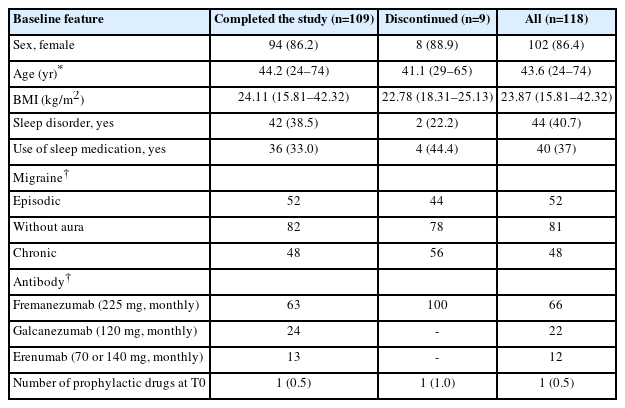

A total of 118 patients were enrolled across 12 centers, with 109 completing the study. Nine participants (7.6%) discontinued the study: three due to treatment inefficacy at the T1 evaluation, and six while lost to follow-up (Figure 1). The cohort was predominantly female (86.4%), with a mean age of 43.6 years (range, 24–74 years) (Table 2).

Patient disposition. Of 118 enrolled patients, 109 completed the study. Nine (7.6%) discontinued: six were lost to follow-up and three due to treatment inefficacy at 3 months.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who completed the study, those who discontinued, and the overall study population

At T0, 40.7% of patients had a diagnosed sleep disorder, with 91% of these cases being Insomnia Disorders. Other reported sleep disorders included: Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders (obstructive sleep apnea), Sleep-Related Movement Disorders (restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder), and Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders (shift work disorder). In what concerns migraine classification, 52% had episodic migraine whereas 48% had chronic migraine. Fremanezumab was the most frequently used mAbs (66%).

No significant T0 differences were found among centers regarding demographic or clinical characteristics (Kruskal–Wallis and chi-square tests, all p>0.1).

2. Changes in sleep quality and daytime sleepiness

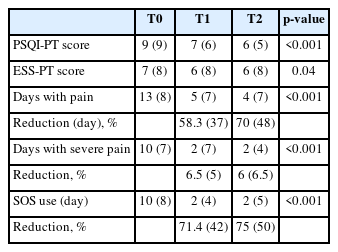

A statistically significant improvement in sleep quality, as assessed by the PSQI-PT, was observed in patients initiating CGRP mAb therapy. The median PSQI-PT score decreased from 9 (IQR: 9) at T0 to 6 (IQR: 5) at T2 (Z=–5.5, p<0.001), suggesting an improvement in subjective sleep quality (Table 3, Figure 2).

Longitudinal changes in sleep quality (PSQI-PT), daytime sleepiness (ESS-PT), and migraine severity at T0, T1, and T2

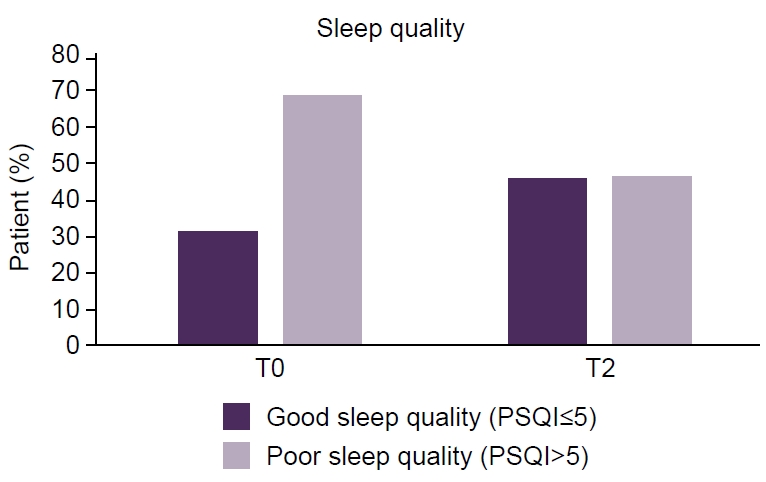

Proportion of patients with clinically defined good sleep quality (Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI-PT] score≤5) versus poor sleep quality (PSQI-PT score>5) at baseline (T0) and after 6 months (T2) of anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody therapy. Sleep quality was assessed using the validated PSQI-PT.

Similarly, a significant reduction in daytime sleepiness, as measured by the ESS-PT, was observed, with the median ESS score decreasing from 7 (IQR: 8) at T0 to 6 (IQR: 8) at T2 (Z=–2.041, p=0.04) (Table 3).

After FDR correction for multiple comparisons, both PSQI-PT (q<0.001) and ESS-PT (q=0.048) improvements remained statistically significant.

3. Treatment effectiveness and its association with sleep quality improvements

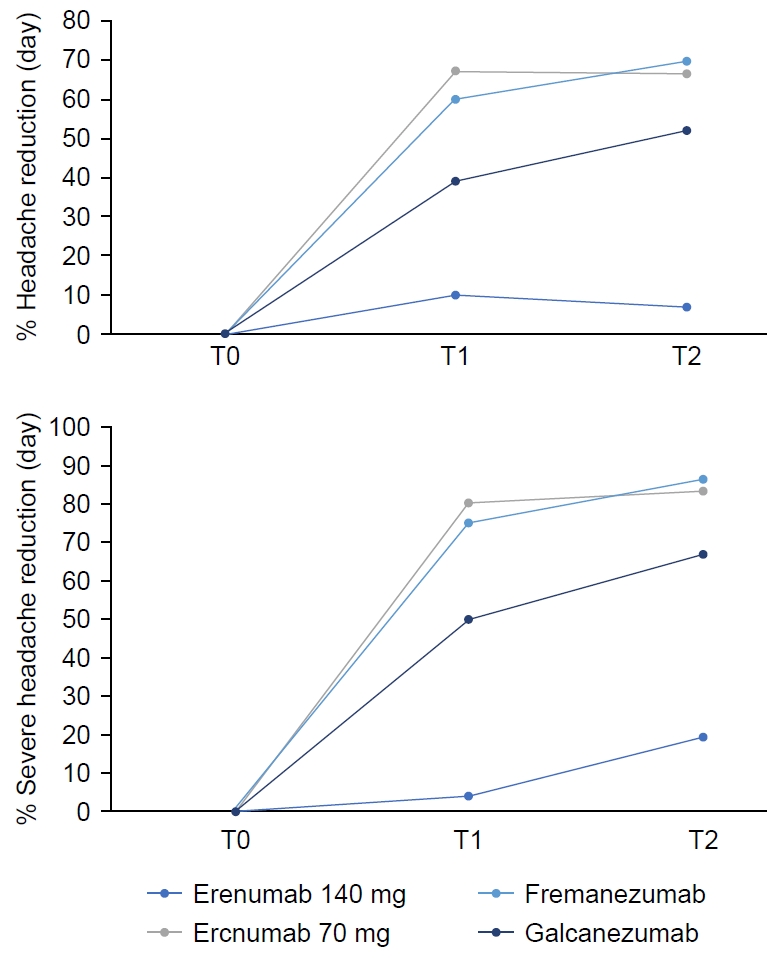

A significant reduction in migraine burden was observed following T2 of anti-CGRP mAb treatment. The median number of headache days per month decreased from 13 (IQR: 8) at T0 to 4 (IQR: 7) at T2 (p<0.001). Additionally, the number of days with severe headache decreased from 10 (IQR: 7) to 2 (IQR: 4) (p<0.001). The use of rescue pain medication (Where there is SOS it should be rescue pain medication) also declined from 10 (IQR: 8) to 2 (IQR: 5) (p<0.001) (Table 3, Figure 3). All p-values remained significant after FDR correction (q<0.001).

Reduction in total headache days (left) and moderate-to-severe migraine days (right) following anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody therapy over time (T0: baseline, T1: 3 months, T2: 6 months). Data are presented as percentage reduction from baseline.

A strong association was observed between treatment efficacy and improvement in sleep quality (p<0.05). Patients who experienced a greater reduction in migraine frequency and severity also showed greater improvements in PSQI-PT scores. However, no significant correlation was found between ESS-PT scores and treatment efficacy (Table 4).

Spearman’s rho for ΔPSQI-PT and reduction in monthly migraine days=0.42, p<0.001 (q=0.002). To control for potential confounders, a multivariate linear regression adjusted for age, sex, BMI, migraine subtype, and sleep medication use confirmed that treatment response remained an independent predictor of ΔPSQI-PT improvement (β=–0.38, p<0.001).

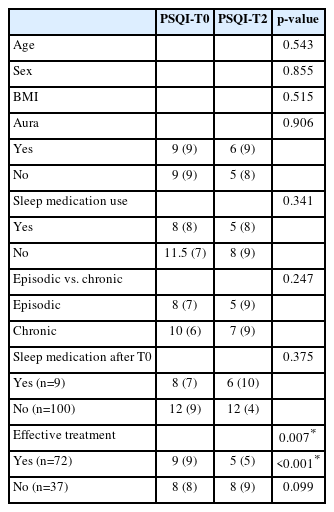

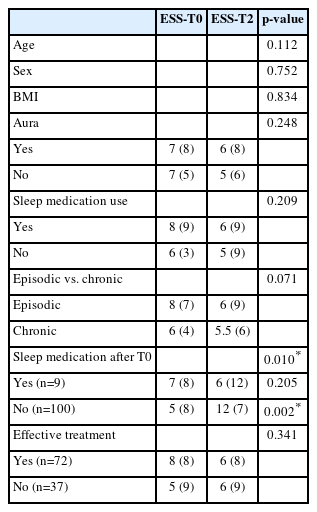

4. Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate potential confounding factors influencing sleep quality and daytime sleepiness. No significant correlations were found between changes in PSQI-PT or ESS-PT scores and age, sex, BMI, migraine subtype (episodic vs. chronic), or aura presence (Table 1).

There was, however, a significant association between ESS-PT score improvement and patients who did not initiate sleep medication (p<0.05) (Table 4).

Furthermore, patients classified as “effective treatment responders” showed a greater improvement in PSQI-PT scores (p<0.001).

After multiple-testing correction, only the association between treatment response and PSQI-PT improvement remained statistically significant (q<0.001). No collinearity was detected among covariates (VIF<2 for all predictors).

Importantly, neither the presence of a pre-existing sleep disorder nor the use of sleep medication significantly modified the magnitude of PSQI-PT or ESS-PT change, suggesting that the observed improvements were consistent across these subgroups.

DISCUSSION

At T0, the majority of patients reported poor sleep quality (Figure 2), though only 40.7% were formally diagnosed with a sleep disorder, with insomnia being the most common. The high prevalence of sleep disturbances in this cohort aligns with existing literature linking migraine and sleep dysfunction,5,6 but also suggests that such conditions could be significantly underdiagnosed.

A key finding of this study is the observation of a statistically significant association between anti-CGRP therapy and sleep quality. The median PSQI-PT score decreased from 9 at T0 to 6 after T2, suggesting that patients who experienced migraine improvement tended to report better sleep quality, rather than demonstrating a direct therapeutic effect on sleep. This finding was particularly evident in patients classified as “effective treatment responders.” However, given the observational nature of the study, these results should be interpreted as associations rather than causal relationships. Although the potential role of CGRP in sleep–wake balance has been proposed, further studies are warranted to clarify whether any direct pharmacological influence might contribute to these associations.

Daytime sleepiness, as measured by the ESS-PT, also showed a statistically significant reduction, though the effect was less pronounced than that observed for sleep quality. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate daytime sleepiness in migraine patients treated with anti-CGRP mAbs. Notably, there was no significant correlation between ESS-PT score improvements and migraine burden reduction. This suggests that the relationship between migraine improvement and daytime alertness is complex and potentially influenced by additional physiological or behavioral factors, rather than a direct medication effect. This finding is particularly intriguing given that CGRP has been hypothesized to play a role in wakefulness regulation in Drosophila.10 In fact, CGRP may influence the circadian cycle by structuring sleep and regulating its rhythm in these animals. Nevertheless, extrapolation of such mechanistic hypotheses from animal models to humans should be made cautiously.

Our data suggests overall that prophylactic migraine treatment with anti-CGRP mAbs is associated with improvements in both subjective sleep quality and daytime sleepiness.

Treatment with anti-CGRP or its receptor mAbs was effective in managing migraine, leading to a reduction in the number of monthly migraine days, the frequency of moderate to severe pain episodes, and the need for acute pain medication. Notably, a sustained improvement in sleep quality, as assessed by the PSQI-PT, was observed at both 3 and 6 months, suggesting a beneficial impact of anti-CGRP therapy on sleep. However, the observed sleep improvements appear to parallel migraine relief, supporting the interpretation that better sleep outcomes are likely mediated indirectly through migraine improvement rather than a direct pharmacological effect of CGRP blockade. While previous studies with smaller sample sizes or shorter follow-up periods have reported similar associations, our results provide a more robust dataset supporting this indirect relationship.11,12,15

Subgroup analysis revealed that improvements in PSQI-PT scores were independent of age, sex, BMI, migraine subtype, or aura presence, indicating that the observed associations were not driven by these demographic or clinical factors. However, a significant association was found between ESS-PT score improvement and the absence of sleep medication initiation. This finding suggests that the use of sleep medication may mask potential improvements in daytime sleepiness, warranting further investigation into the interaction between migraine treatment and pharmacological sleep interventions.

The findings of this study have important clinical implications emphasizing the association between reduced migraine burden and better subjective sleep quality in patients treated with anti-CGRP mAbs, rather than implying a direct therapeutic sleep effect. Given the high prevalence of sleep disturbances in migraine patients, routine assessment of sleep parameters in clinical practice may enhance patient management and optimize treatment outcomes.

Despite the strengths of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study relied on subjective sleep measures (PSQI-PT and ESS-PT), which, while validated, may not fully capture objective sleep architecture changes. Future research should integrate polysomnography or actigraphy to assess the associations between anti-CGRP therapy and sleep patterns more accurately. Additionally, potential confounders, such as medication adherence and comorbid psychiatric conditions (e.g., anxiety and depression), were not extensively analysed, which could influence sleep outcomes. Another consideration is that approximately 40% of participants had a pre-existing sleep disorder and 37% reported using sleep medication. While the latter variable was included as a covariate in multivariate analyses, T0 sleep disorder diagnosis was not formally modeled due to heterogeneity of conditions and small subgroup sizes. Nonetheless, subgroup comparisons revealed no significant interaction between these factors and changes in PSQI or ESS, suggesting that they did not substantially bias the observed improvements. Moreover, as within-subject change scores inherently account for T0 PSQI and ESS levels, residual confounding by T0 severity is expected to be minimal.

Future studies should explore the mechanistic links between migraine relief and sleep improvements, including the role of neuropeptides such as CGRP in sleep regulation.

Additionally, longitudinal studies with objective sleep assessments, such as polysomnography, may provide deeper insights into the relationship between anti-CGRP therapy and sleep architecture and circadian rhythms.

1. Conclusions

This study reports a significant association between anti-CGRP mAb therapy and improved sleep quality in migraine patients, primarily in parallel with reductions in migraine burden. While our findings do not confirm a direct pharmacological effect of anti-CGRP therapy on sleep regulation, they reinforce the potential role of migraine treatment in addressing sleep disturbances.

Notably, daytime sleepiness also showed improvement over the study period, independently of treatment response and despite the limited blood-brain barrier penetration of anti-CGRP therapy, suggesting a physiological interaction between migraine pathophysiology and sleep–wake regulation.

Given the larger sample size and extended follow-up period compared to prior studies, our results offer robust support for these observed associations. These findings also underscore the intricate relationship between migraine and sleep disturbances and suggest that optimizing migraine treatment may have far-reaching benefits for sleep health, regardless of migraine type. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise mechanisms underlying these associations. Objective sleep measures such as polysomnography and actigraphy could provide deeper insights into how migraine improvement correlates with changes in sleep quality. A deeper understanding of CGRP’s role in sleep-wake regulation could not only refine migraine treatment but also unlock new therapeutic strategies for sleep disorders. As CGRP-targeted therapies continue to evolve, their potential impact on both migraine burden and sleep health warrants further exploration.

Notes

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: RC, AF, BM, CF, HD, EP, FP; Data curation: all authors; Formal analysis: RC, AF, BM, CF, HD, EP, FP; Investigation: RC, AF, BM, CF, HD, EP, FP; Methodology: RC, AF, BM, CF, HD, EP, FP; Supervision: HD, EP, FP, Validation: HD, EP, FP; Writing–original draft: RC, AF, BM, CF, SP, CG, CM, DV, MM, JS, MSD, SC, MB, ALR, HD, EP, FP; Writing–review & editing: RC, AF, BM, CF, SP, CG, CM, DV, MM, JS, MSD, SC, MB, ALR, HD, EP, FP.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all participating patients and the clinical teams from the twelve collaborating headache centers for their invaluable contribution to data collection and follow-up.