Headache as a Somatic Symptom in Pediatrics: Diagnosis and Integrated Management

Article information

Abstract

Somatization—the expression of psychological distress through physical symptoms—presents a frequent and complex challenge in pediatric practice. Headache and dizziness are among its most common manifestations. This review addresses the diagnostic challenge of determining whether these symptoms indicate a primary headache disorder or reflect somatic symptom presentations. The difficulty becomes particularly evident when conditions manifest in severe or persistent forms, such as chronic primary headache (CPH) and somatic symptom and related disorders (SSRD), where clinical overlap is considerable and coexistence may occur. We first explore the shared pathophysiological mechanisms, emphasizing central sensitization as a unifying process. We then propose a clinical framework for differential diagnosis that includes careful evaluation of predisposing risk factors and contrasts the defined diagnostic criteria of CPH with the maladaptive psychological responses frequently observed in SSRD. Management strategies diverge pharmacologically but converge on key non-pharmacological approaches. For primary headaches, pharmacotherapy is primarily used for prophylaxis, although its efficacy remains limited in pediatric trials. In contrast, for somatic presentations, medication typically serves as an adjunctive treatment targeting comorbidities, while psychotherapy (particularly cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT]) functions as the cornerstone of care. Non-pharmacological interventions such as CBT and biofeedback are essential for improving functioning across both conditions. Therefore, effective management relies on a framework of comprehensive psychoeducation, holistic assessment, and integrated interdisciplinary care.

INTRODUCTION

Somatization, defined as the expression of psychological distress through physical symptoms, is a frequent and complex challenge in pediatric clinical practice.1 Instead of verbalizing emotions such as anxiety or stress, children and adolescents may present with significant somatic complaints. Importantly, these symptoms are not feigned; the suffering is genuine and can cause substantial functional impairment, including chronic school absenteeism.2 The tendency toward somatic expression is often shaped by a confluence of factors, ranging from individual psychological vulnerabilities and prior life experiences to socio-environmental pressures like family stress, highly competitive environments, or cultural contexts that discourage emotional disclosure.3

These manifestations exist along a spectrum of severity. At one end are transient functional symptoms that resolve spontaneously with minimal disruption; at the other are persistent, disabling presentations that may fulfill the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for somatic symptom and related disorders (SSRD).4,5 This spectrum naturally provokes varying levels of parental concern and requires tailored clinical intervention. Headache and dizziness are among the most common medically unexplained symptoms in this population. Their considerable clinical overlap with primary headache disorders creates significant diagnostic challenges—particularly in children, whose headache characteristics are often less distinct than in adults.6

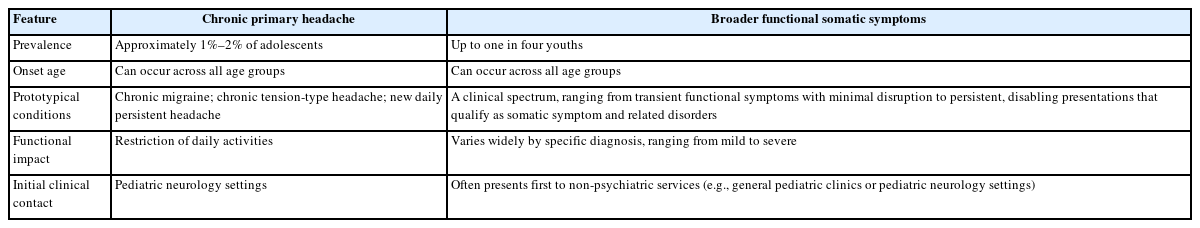

Prevalence data highlight the scale of these conditions: while chronic primary headache (CPH) affects approximately 1%–2% of adolescents,7 broader functional somatic symptoms occur in up to one in four youths.8 To clarify this clinical context and severity spectrum, Table 1 provides a comparative summary of the key characteristics and functional impact associated with both conditions in the pediatric population.

Comparative summary of chronic primary headache and broader functional somatic symptoms in pediatric patients

Because these symptoms frequently present first to non-psychiatric services, insufficient recognition at the initial encounter may result in extensive diagnostic testing and medication-centered management strategies that are often ineffective.9 Understanding the interplay between primary headache disorders and somatic symptom presentations is therefore essential for all clinicians caring for pediatric patients.

Therefore, a critical need exists for the integration of the primary headache and SSRD frameworks, which specifically emphasizes shared central sensitization (CS) as a unifying mechanism. This transdiagnostic perspective facilitates clearer clinical differentiation and underscores the necessity of integrated care models.

Moreover, these cases frequently strain the physician–family relationship, underscoring the need for clear communication and integrated care. Against this background, the present review aims to assist clinicians by examining shared pathophysiological mechanisms, identifying risk factors for somatization in youth, differentiating between CPH and somatic symptom presentations, and outlining management strategies, highlighting differences in pharmacological approaches and similarities in non-pharmacological ones.

A SHARED PATHOPHYSIOLOGY: THE SENSITIZED BRAIN

Building on the clinical overlap described in the introduction, a substantial pathophysiological convergence exists between the chronification of primary headaches and SSRD. CS has emerged as the key unifying mechanism linking these conditions.10,11 CS reflects a state of amplified neural signaling within the central nervous system, producing heightened pain sensitivity and characteristic features such as allodynia and hyperalgesia.10 Notably, migraine—a prototypical primary headache disorder—shares this sensitization pathway with functional somatic syndromes and psychiatric comorbidities, underscoring its transdiagnostic importance.11

Children and adolescents may be particularly susceptible to maladaptive sensitization due to their neuroplasticity and ongoing brain maturation.12 Pediatric neuroimaging studies reveal altered connectivity within pain-related networks and disrupted resting-state activity, suggesting that the developing brain is vulnerable to long-term functional reorganization.12

Biopsychosocial factors further shape this sensitized state. Childhood maltreatment and early life stress have been shown to program lasting dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and to trigger low-grade systemic inflammation, thereby increasing vulnerability to chronic pain conditions.13,14 In adolescence, the surge of gonadal hormones contributes additional instability by reorganizing neural circuits that govern both emotion regulation and nociception.15

At the systems level, convergent processing of emotional and sensory signals in the anterior cingulate cortex and insula provides a structural substrate for cross-sensitization.12 During neurodevelopment, these circuits remain plastic, and persistent activation by psychological distress can more readily “spill over” into adjacent pain-processing networks, reinforcing a cycle of symptom chronification.16

For instance, when prolonged psychological distress is processed in key emotional areas like the insula, the resulting chronic activation allows the emotional signal to “spill over” into adjacent pain-processing networks. This crossover leads to the misinterpretation of harmless inputs—such as minor muscle tension or light touch—causing them to be experienced as severe pain signals and ultimately manifesting as increased headache frequency or severity.

Taken together, these findings suggest that pediatric pain syndromes are rooted in CS within the developing nervous system, rather than being purely psychogenic.

RISK FACTORS FOR SOMATIZATION IN YOUTH

The emergence of somatic symptoms in children and adolescents reflects the interplay of biopsychosocial risk factors. At the individual level, vulnerability may arise from psychological predispositions such as high anxiety sensitivity, neuroticism, and perfectionism, some of which have a genetic basis.17,18 Comorbid psychiatric conditions—especially anxiety and depressive disorders—are also strong predictors, as is alexithymia, the difficulty in identifying and describing emotions.19

These risks can be amplified by previous adverse experiences, including serious medical illness, trauma, or neglect, which heighten sensitivity to bodily sensations.20

Socio-environmental stressors further shape these predispositions. Within the family, parental modeling of illness behavior, high level of family stress, and overprotective parenting exert strong influence.21 In schools, academic and social pressures may add to the burden, while cultural norms that discourage emotional expression can further reinforce somatic tendencies.22

Once established, symptoms persist through reinforcing mechanisms, as the sick role is maintained by secondary gains like increased attention or relief from stressors.20

CLINICAL DIFFERENTIATION OF PRIMARY HEADACHE DISORDERS AND HEADACHE AS A SOMATIC SYMPTOM

Differentiating between primary headache disorders and headache presenting as a somatic symptom is a significant clinical challenge, given their considerable phenomenological and pathophysiological overlap.

The diagnosis of CPH—including chronic migraine, chronic tension-type headache, new daily persistent headache (NDPH), and medication overuse headache (MOH)—is established according to the objective criteria outlined in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3).23 For instance, chronic migraine is defined by headache on ≥15 days per month, with migrainous features on at least 8 of those days. Clinically, patients with SSRD may present with headache patterns that closely mimic these primary disorders. In particular, the abrupt and unremitting pain of NDPH or the analgesic-driven progression into MOH may resemble the headache presentations seen in SSRD.24

When diagnosing headache as a manifestation of SSRD, the diagnosis is not based on specific headache features—which are often vague, atypical, and notably not outlined in the DSM-5 criteria—but instead relies on the patient’s excessive and maladaptive psychological responses as defined by those criteria.5,25 Clinically, SSRD expresses itself in ways that significantly amplify the headache experience, such as pain amplification, chronic, high-level health anxiety centered on the head (e.g., fear of tumor despite clear scans), or functional neurological presentations like unexplained neurological deficits (e.g., transient blindness or severe imbalance during a headache). Diagnostic clues include disproportionate thoughts, emotions, and behaviors related to the headache, such as pain catastrophizing and significant functional impairment. Patients with SSRD typically emphasize these maladaptive responses—particularly the disabling impact of symptoms and associated emotional distress.26

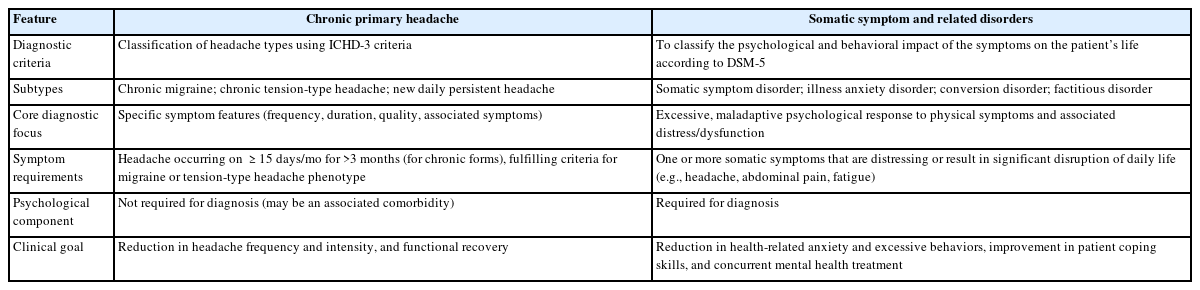

Notably, not all patients express distress overtly; many exhibit alexithymia, a difficulty in recognizing and articulating emotions, which may result in emotional numbing or poor awareness of discomfort.19 Such presentations require careful clinical attention, as they can obscure the psychological drivers of symptoms. Additional indicators include the presence of multiple medically unexplained symptoms beyond headache and a tendency toward “symptom shifting.”26 The essential differences in the diagnostic focus between CPH and SSRD are summarized in Table 2.

Diagnostic clarity becomes especially challenging when CPH and SSRD coexist. This comorbidity may create a vicious cycle of mutual reinforcement, whereby psychological distress lowers the pain threshold while chronic pain exacerbates psychological symptoms.27 This complexity is further compounded by differences in diagnostic frameworks (DSM-5 for SSRD versus ICHD-3 for “headache attributed to a psychiatric disorder”), underscoring the importance of interdisciplinary awareness. Because patients typically present with headache as the primary complaint, the underlying psychiatric contribution may easily be overlooked unless specifically considered.28

PHARMACOLOGICAL DIVERGENCE AND NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL CONVERGENCE

Although pharmacological approaches differ between primary headache disorders and somatic symptom presentations, there is clear convergence in the value of non-pharmacological interventions. Across both conditions, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has consistently demonstrated efficacy in reducing symptom burden, functional impairment, and healthcare utilization by reframing maladaptive thoughts and enhancing coping strategies.29,30 Biofeedback, by providing real-time awareness of physiological processes, has likewise been reported to promote self-regulation and reduce symptom frequency and intensity.31,32

The primary distinction lies in pharmacological strategy. Treatment of primary headache disorders typically emphasizes prophylaxis with agents such as anticonvulsants (e.g., topiramate) or beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol) to decrease headache frequency and severity.33 However, in pediatric and adolescent populations, evidence indicates that the efficacy of pharmacological prophylaxis is limited. The Childhood and Adolescent Migraine Prevention trial demonstrated that neither topiramate nor amitriptyline was superior to placebo in reducing headache frequency, underscoring the limitations of medication-based strategies in this age group.34 This limitation highlights that a poor response to medication should prompt clinicians to look beyond purely pharmacological strategies, considering both the possibility of headache as a somatic expression and the integration of non-pharmacological therapies.

By contrast, the cornerstone of treatment for somatic symptom presentations is psychotherapy—most notably CBT—which prioritizes functional improvement rather than complete symptom elimination. Pharmacotherapy, most often with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, is typically adjunctive and directed toward comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders.35

Effective management strategies are best supported by the following principles:1,36

• Providing comprehensive psychoeducation: Clear communication that enhances patient and family understanding of the diagnosis is fundamental for improving adherence and achieving long-term outcomes.

• Conducting holistic assessment: Clinicians must extend evaluation beyond the presenting complaint to identify comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions that may require additional support.

• Fostering interdisciplinary collaboration: Optimal care depends on coordinated input from neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and allied health professionals. Importantly, a patient’s differing responses to various interventions may itself provide valuable diagnostic insight.

CONCLUSION

Headache and dizziness in children often blur the distinction between primary headache disorders and somatic symptom presentations. CS offers a shared neurobiological framework, yet primary headaches are defined by ICHD-3 criteria, whereas somatic symptom disorders are characterized by maladaptive psychological responses, frequently complicated by alexithymia and psychiatric comorbidities.

Management diverges in pharmacological strategies but converges in non-pharmacological approaches. Pediatric trials demonstrating the limited efficacy of preventive medications underscore the importance of psychotherapy and integrated, function-oriented care.

Effective management may therefore require early recognition of somatic presentations, avoidance of unnecessary investigations, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Future research should focus on refining diagnostic clarity and treatment efficacy by prioritizing several key areas. Specifically, research efforts should be directed toward the validation of pediatric-specific diagnostic tools that consider both ICHD-3 and DSM-5 criteria, conducting longitudinal studies to map the trajectory and prognosis of somatic symptom presentations, and performing rigorous evaluation of integrated programs to establish best practices for holistic care and optimized outcomes for affected youth.

Notes

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: HEK; Writing–original draft: HEK; Writing–review & editing: HEK.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Hye Eun Kwon is the Editor of Headache and Pain Research and was not involved in the review process of this article. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.